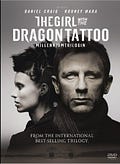

I’ve been reading the Millennium trilogy by Stieg Larsson; feeling my creative batteries in need of a serious recharge, I had retreated into a reading cocoon, and his original 3-book series seemed promising. I saw the American movie of the first book The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo which I thought quite well done—LOVE Rooney Mara, loved Carol—so when I …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to FORD KNOWS to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.